Inside Acoustic Music: Recording a Live CD — Pt 3

Tech Talk with Siiri Metsar

Posted Wednesday, September 3, 2008

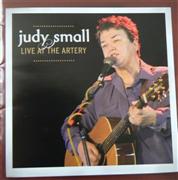

In an intimate gallery/performance space, on a narrow Melbourne backstreet, over two consecutive nights of a summer that was to be extremely hot, an Australian singer/songwriter finally recorded her first live album. This is the third part of a four part article that tells the story of the making of Judy Small: Live at The Artery. And audio engineer/producer Siiri Metsar is a key part of the story.

JUDY SMALL (www.judysmall.com.au) is an Australian singer/songwriter, who also works as a lawyer specialising in family law.

SIIRI METSAR has been twiddling knobs in recording studios and on live mixing consoles for nearly two decades, during which time she has continued to build a strong reputation as Australia’s only specialist audio engineer/producer in folk, world and acoustic music. Siiri’s credits as a producer and audio engineer include two albums by Judy Small — Let the Rainbow Shine (1999) and Judy Small: Live at The Artery (2007).

When interviewed a few years ago for the article, ‘Revelation in the Studio: Women Producers and Engineers’, Siiri Metsar had advice for performers about choosing a producer an engineer and a studio. And she recently reiterated that advice…

“Production is such an individual, personal thing, that having the wrong producer can totally destroy a project. Having the right one can take the project to a new dimension. My advice would be not to have a producer unless you are sure you want one, and then to go along with the producer’s advice wholeheartedly. Too many bands like the idea of hiring a producer, but then find that they think they know better anyway, so the whole project ends up in arguments and ill feeling.

“It is important that the producer and/or engineer you choose will at least be sympathetic to your style of music. Talk to the person, listen to the material they have worked on before and get a feel for the person. See if you feel you can trust that person and whether you would feel comfortable baring your soul to that person in a confined area for many hours at a stretch!

“In choosing a studio, shop around, compare prices and facilities. However, do look beyond the aesthetics of a studio and delve into those deeper issues of microphone selection, whether it’s a digital or analogue desk for mixdown, outboard gear and studio acoustics. And, of course, check out how many types of tea they have on offer and whether there’s a cappuccino machine!!!”

Siiri now reflects on the making of Judy Small: Live at The Artery and provides advice on recording a live CD…

Pros and cons of a live album

“In the studio, there is a large degree of control over many aspects of the recording, from the ability to select and modify the microphones used and their placement, to selecting suitable acoustic spaces, to being able to repeat sections or parts until they are right, or revisiting parts at a later date to modify or improve them. In the studio, the musicians use headphones to prevent spill from the monitoring entering the recording, so you have greater scope in the mixing process for placing, separating and treating the individual sounds.

“Many of these factors diminish or disappear altogether in a live recording. It is not always easy to anticipate the sorts of problems that can arise in a live setting, and once the recording is done, the choices in modifying the material or fixing any problems will be limited.

"A lot of people who attempt a live recording do so because they feel that a studio recording doesn’t capture the energy or ‘vibe’ of their live performance, but this can be an illusion! What seems like a great performance to the band and/or the audience at the time can, on playback, sound greatly flawed. When a musician is performing at a gig, many senses are being used, from the visual to the auditory — even the sense of being in the moment — and all of these add to the experience of the performance. Later, when all other stimuli are removed, and all that’s left is the auditory experience, it may not measure up. When a musician makes a small mistake at a gig, it exists in a single moment and is quickly forgotten. On a recording, it lives on and on. Under certain circumstances, some of these mistakes can be repaired or fixed later at the studio, but where the material is fundamentally flawed (for example, a song speeding up, or a musician dropping a beat or being out of tune, or if there is feedback on the recording) then you may find that by the time you’ve replaced all the flawed bits, you have recorded the whole piece anew in the studio anyway!”

Live, but listenable

“It’s very important for a live album to be listenable, otherwise it’s in danger of just becoming simply an ‘archive’ — which may in itself be or not be relevant, depending on the goal of the recording artist and the listener. For example, if the songs on the recording are punctuated by too much idle chatter or in-joking, or the applause is too loud or too long, or if there are other interruptions like tuning or heckling, then it might become tedious and won’t get taken out for a listen very often by someone wanting to listen to a collection of songs. However, if the aim is to make an archival type of album that documents a particular point in an artist’s career, or a particular landmark event or venue, then it may not be listened to very often, but may still be a valuable memento to a listener.

“I think it’s important for the artist to have a goal or an angle with the live album. For example, when I recorded Penelope Swales’ Live at Woodford ’96-’97, her aim was to record live all of the long and intricate stories that accompanied some of her songs at the time, mainly as a final record of many of the stories and songs that she would no longer be performing live, as she was ready to move on into new material, but was nevertheless constantly getting requests for from her audience.”

Making or breaking a recording session

“There are two main factors that can make or break a recording session. The first of these is being prepared. There is no point in entering the studio if you don’t have a clear idea of what you are intending to achieve, or how you are going to go about it. If your ideas or your songs are half-baked, then the recording sessions will be a nightmare of endless options but little form. Of course, not everyone is fully experienced in recording, and it takes practice — just like everything else — to get good at it, but by talking to other musicians and the engineer you intend to use, you can get a pretty good idea of how to approach the recording, and the ways in which you can prepare. There are no shortcuts to good rehearsals and there are no excuses for entering the studio under-rehearsed!

“The other factor that can get in the way of a good recording is being overly precious in the studio. You have to go with the flow in the studio, and by getting overly precious about things, it can hinder the outcome of the recording and can certainly destroy everyone else’s enjoyment of the studio experience. It’s good to have a degree of attention to detail, but at the end of the day, a recording is a kind of snapshot of your abilities and your ideas at the time. It may not be perfect, but if you have made the best album you can at the time, it’s more important and valuable to put it out there, have people listen to it and move on, than it is to strive for some idea of ‘perfection’, or to cling to ideas that aren’t working. You’d be amazed how often I have to remind musicians that unless they release their first album, they’ll never be able to release their second one!”

Preparing for a recording session

“Preparation for a recording session depends on the recording and the performer. Sometimes my preparation, as the engineer, is nothing more than agreeing over the phone on some dates and times, and then meeting up in the studio to begin recording! Usually, I like to get a demo recording, or see the performer live to get an idea of the material if I’m not familiar with the music, and generally I will have a meeting with the performers so that we can get to know each other, and also to answer any questions or concerns they may have. Sometimes, if it’s a band I’ve worked with before, we may have dinner or go out for a drink, more with a social angle rather than a technical one, to have a chat and get a good rapport going before the sessions begin.

“I like to know ahead of time what the line-up is going to be, whether the band intends to record the beds ‘live’ in the studio (i.e. all together), or put down a guide and then multitrack one instrument at a time, and what their time-frame is in general terms of getting the project finished. I try not to over-prepare myself, as I don’t think it’s wise for me to have too many pre-conceived ideas about someone else’s music before entering the studio, and I think it’s far better to go with the flow and to use my instincts instead. Most of the time you can deal with situations or problems as they arise.”

Tech specs

“There weren’t too many technical specifications as such for Judy’s concerts, and the setup was actually quite simple. My main goal for Judy’s shows was to make sure that the live sound was going to be good, so that we wouldn’t have any technical problems, but also so that the musicians would all be relaxed and confident, and could focus on their playing. I wanted to take charge of doing the live sound myself, and delegated the task of recording to my assistant, David Swinton. I kept everything on stage to a minimum, and tried not to overcomplicate anything.

“In order to get best separation and the cleanest sound, I decided to use the pickups in the instruments, so the two guitars (Judy’s and Kate Burke’s), the violin, the mandolin, and Kate’s small guitar were all recorded via their pickups. I know that it’s not the most ideal sound for a recording, but I figured that the separation, and therefore my scope in equalising and treating the sound later in the studio, would more than compensate for the compromise in sound, and in hindsight, after having mixed the album, I think that theory held true. I did put up a microphone on Judy’s guitar as well (a Shure SM-57), but because she wasn’t used to having her guitar miked at a gig, she moved around quite a bit, and it was hard to control the tone off the guitar through this channel. The mic also picked up quite a lot of the foldback, so was a bit murky in sound, but still proved to be useful, as Judy’s guitar pickup sounds a lot more ‘zingy’ than Kate’s, and blending in some of the microphone added a bit of warmth to the sound.

“I used good old Shure SM-58s on the vocals because they are rugged and forgiving and generally sound pretty good on all kinds of different voices. There was a bit of proximity effect on Judy’s voice on the recording (a boominess that happens when you sing very close on the microphone), and there was some popping as well, but these were quite easy to deal with later in the studio, and I was pleasantly surprised by the quality in general. We had three vocal mics up, one each for Judy, Kate and Matthew Arnold, plus three extra mics off to the side for the guest singers.

“Finally we had two audience mics up to capture the applause, some ‘spontaneous’ sing-alongs, and audience reactions to jokes and stories. In all we had thirteen channels, split out of the live mixing desk and recorded straight to Protools, and monitored very simply on screen and via headphones. I recorded a CD also straight off the desk as a listening reference CD, but also I guess as an emergency backup in case we had a glitch, or lost some data, although we would not have the ability to multitrack mix this version.

“For the live mix, I used a Soundcraft ‘Spirit’ 16-channel desk, with two ARX Powermax-2 (15”+horn) speakers on stands for front-of-house, with two sends of foldback consisting of 4 x ARX Powermax-3 (12”+horn) speakers. We kept one send of foldback just for Judy and the other send was split between Kate and Matthew, and the guest backing singers when they were on stage. I use ARX SX-3000 amplifiers and ARX EQ-60s for graphic EQ all round. The live sound setup was effective, although simple and compact. This way the sound would be tight and clear, but without interfering overly with our recording.”

Crucial elements

“The most crucial element in a live recording is that the tape keeps rolling! Or in more current terms, that the computer keeps recording. This is the one and most important element, and that is why I would never attempt to do the live sound and the recording at the same time myself. Someone needs to sit and watch the recording 100% of the time so that it doesn’t crash or stop recording. Luckily we didn’t have a computer crash or a power failure, as this could be disastrous in a live recording to computer.

“It’s also important to make sure that none of the instruments themselves stop working (for example due to a faulty guitar lead, or the musician accidentally unpugging themselves).

“Also fundamentally important is that the PA is well-tuned for the live gig, so that there is no feedback or coloration to the sound from ringing frequencies.”

Oops!

“It would generally take a considerable disaster for me to stop a gig mid-flow and make a suggestion! The only thing I can think of is if the computer crashed or stopped recording and we had to start a song or a section again — but even then I would wait until the interval or the end of the gig to suggest doing the song again. If there was a technical problem that we couldn’t resolve immediately (for example a guitar pickup that suddenly stopped working), then I would possibly recommend a short interval while we sorted it out, but I would generally make sure that everything that could go wrong was sorted out in the soundcheck.”

From raw recording to finished album

“After a live concert is recorded, there are three further steps involved before it becomes an album.

"The first step is listening to the material and deciding which songs to include and which ones to leave out. It’s important to bear in mind the general flow of the album and the goal of the live recording in general. In this step you can decide which stories or heckles or jokes are worth keeping, if any. I believe that this step should be done entirely by the performer in their own time. I might later give some feedback or make further suggestions, but I believe that choosing the songs to be included is the realm of the performer, as it will define the shape and feel of their album, and they may have very personal reasons for choosing or discarding a particular song. They are paying for the album and they need to be the ones to decide what should be on the album.

“The next step of the process is mixing the tracks in the studio. Again, it’s very important that the artist is present during this process, as they may hear things that they do or don’t like, or want the balance a particular way, or I may make suggestions, or do edits, for which I need their sanction in order to proceed.

“The final step is mastering, which involves putting all the individual songs in order (if they aren’t already in order), smoothing out the gaps or the applause between tracks, including any cross-fades or segues, and making sure that the overall levels of each individual song are consistent across the album. The mastering engineer can also add some ‘fairy dust’ to the recording by way of enhancing frequencies, adding clarity in the top end and smoothing out any lumps in the bottom end. Any overall problems in tone can be ironed out in this process, providing they’re not too serious. It is in the mastering also that you will need to define exactly where each track actually begins on your CD player, which on a live recording may not be as straightforward as on a normal album, as talking or applause may overlap with the start or the end of a song.

“On Judy’s album we decided to put the stories as pause tracks — or in other words, as negative numbers leading up to the song, which starts at zero. If you want to listen to a particular song, you just hit the track number of that song, and you go straight into the song, but if you’re listening to the album as a whole, you will hear all the stories as well. One advantage to keeping the stories or talking separate from the songs is that you may get some airplay if the songs are compact and to the point.

"Martin Pullan from Edensound Mastering in South Melbourne (www.edensound.com) has been doing my mastering for over ten years and he understands my aesthetics of acoustic music.

“Judy was in great voice on the two nights at The Artery, and although I’ve never been a big fan of live recordings, I think this one does actually shine!”

SUE BARRETT was in the audience on 1 and 2 December 2006 when Judy Small: Live at The Artery was recorded. An earlier article, ‘Revelation in the Studio: Women Producers and Engineers’ (Jen Anderson, Tret Fure, Leslie Ann Jones, Karen Kane, Joan Lowe, Siiri Metsar, Susan Rogers, Darleen Wilson), can be found here www.femmusic.com/interviews%202001/theproducers.htm

© 2008