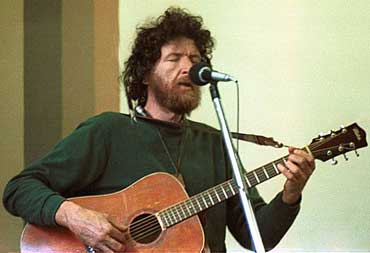

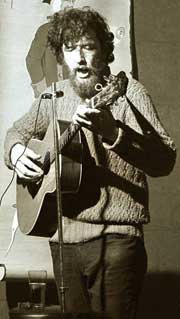

Declan Affley - A rake & rambling man

A tribute after 20 years

Posted Friday, June 3, 2005

Declan Affley's sudden death on the 27th June, 1985, at the age of 45, shocked everyone who knew and admired him as a person and an outstanding folk singer and musician.

Declan was born in Cardiff, South Wales, 8th September, 1939, to an Irish/Welsh Catholic working class family. The Affleys were from Cork and his mother, mainly descended from Welsh miners, also had some Cork ancestry. Declan grew up in Splott, where many of the extended family lived. He attended St Alban's and later St.Illtyd's Catholic Schools, but maintained they "didn't produce lasting damage". Irish Catholics tended to stick together in predominantly Methodist Wales and many family holidays were spent in Cork. Later the family moved to Rumney.

Declan excelled at the clarinet and was in the St.Alban's band, which played for many events, including football games in Cardiff Arms Park. Later he was a member of the Cardiff College of Music's orchestra. Aged sixteen, after completing his Leaving Certificate, he joined the British Merchant Navy.

Some of Declan's earliest memories were of his dad playing the Scots pipes at St. Patrick's Day marches and attending Irish Ceilidhs at St. David's Parish hall. His father listened to traditional Irish music on RTE, Ireland's public broadcaster, and sang at many functions. Declan learnt many songs from him including 'Crushkeen Lan'.

In 1956, on his first visit to Japan, as a seaman, he purchased "a hideous machine somewhat resembling a guitar", and taught himself to play, and accompany himself on folksongs.

Declan rose to the rank of Second Mate before jumping ship and coming to live in Australia in 1959. He told me he'd fallen in love with Geraldton in WA, when his ship docked there. Based in Sydney he worked on east coast ships as an AB (able bodied seaman).

Whilst on shore leave he sang in 'low dives and pubs', such as the Royal George, Sydney and Tattersalls in Melbourne. Irish rebel songs and other folksongs were sung with great gusto in these pubs and it was here that Declan met singers such a Brian Mooney, Don Ayrton, Paul Marks and Martin Wyndham-Read.

Declan eventually became a regular performer at the Troubadour Coffee Lounge in Edgecliff, Sydney and later at Frank Traynor's Folk Club, Melbourne. He was also a frequent guest at the 'Greenwich Village', the Elizabeth Hotel – 'the Liz', Pact Folk, Edinburgh Castle and other Sydney folk venues. He also became a stalwart of the •rst folk clubs in pubs in Melbourne in the late 1960s such as Fogarty's – according to John O'Leary, Declan, after singing for most of the opening Saturday afternoon, received the princely sum of $4.00, and later the Dan O'Connell Hotel, Carlton.

He was also a familiar face at national and local folk festivals and toured Indonesia, New Guinea and New Zealand.

Irish music sessions included the Gaelic Club and Wentworth Park Hotel, Ultimo, with hospitable publicans, Tommy and Joan Doyle. Declan played and socialised with many Irish musicians.

He was well known for his singing, his deep resonant voice, subtle guitar accompaniments, which he said were based on an appreciation of the Irish Harp, and for witty, pithy commentaries between songs. Ardent about traditional music, in particular the Irish, he also sang many British Isles songs, and was interested in a wide variety of musical styles. His extensive repertoire also included Australian and New Zealand traditional songs and songs by contemporary songwriters such as Don Henderson, Harry Robertson and John Dengate.

He was creative in his interpretation of folksongs. The transportation ballad 'Jim Jones' was usually sung to an upbeat tempo but by slowing it right down Declan highlighted its strong rebellious and dramatic tone. He's probably best remembered for his rendition of Irish folk song 'Carrickfergus', although he also had a special af•nity with songs such as 'An bunnan Bui – The Yellow Bittern' and 'Do you think that I do no know', a Henry Lawson poem, set to music by Chris Kempster.

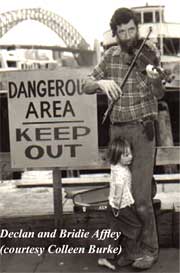

As well as guitar, Declan played tin whistle and banjo and in 1967 taught himself the •ddle from tapes of Irish • ddle player Johnny Doherty.

In 1970 Sydney's Irish community lent Declan a B flat set of uillean pipes made by Harrington of Cork. This event marked a major turning point in his musical career. In Ireland uillean pipe playing was part of a continuing tradition, but in Australia Declan was isolated. He contacted oboe players for hints on reed making, where to buy cane, generally pestering anyone who could help him. The pipes became his passion - he was forever fixing them up - forever trying to make the perfect reed. He would say - "Listen Burkie I've got it!- Ah, I'll just take a little bit off here and here. Wrecked. Back to square one."

In 1972 he toured Ireland with Peter O'Shaugnessy and Marion Henderson in The Restless Years, a dramatic production of Australian history illustrated by stories, poems, folksongs and anecdotes based on the award winning ABC TV program, which he also sang and played in. Their starting point was the Dublin Theatre Festival.

Some of the Irish pipers that Declan most admired were Seamus Ennis, Willie Clancy and Dan Dowd. Whilst in Dublin he sought out Dan Dowd and spent hours with him learning how to make reeds and the intricacies of the pipes. We also spent a night with Willie Clancy locked in a pub in Milltown Malbay, Clare.

Blessed with the gift of the gab Declan could discourse for hours on topics as diverse as history, music, politics, cricket and all footy codes.

Profoundly egalitarian he scorned all pretension and bullshit, was modest about his achievements, and never sought fame or money for his music. He had the rare ability to share his musical knowledge and to inspire others. He encouraged people to sing and play, passing on musical skills to anyone who was interested.

In 1984/5 Declan taught fiddle and banjo at the Eora Centre, an Aboriginal Cultural Centre in Redfern, Sydney.

As well as being involved in radio and TV programs, Declan also appeared in several •lms including Peter Weir's The Last Wave, and Richard Lowenstein's Strikebound, where he was musical director as well as having an acting role and singing songs such as "The blackleg miner".

An exceptional solo performer, Declan also played with many bands. He started the group 'The Wild Colonial Boys' in Melbourne in 1969, which combined Irish and Australian music. He convinced Bob McInnes, Jim Fingleton (Canberra) and Jacko Kevans (then Sydney based) to put their lives on hold and move to Melbourne to join the band. The other band member was Irish singer Tony Lavin. 'The Wild Colonial Boys' became the standard model for many successive Aussie folk bands. Declan and band members appeared in Tony Richardson's 'Ned Kelly' film.

Although not a joiner of political parties or groups, Declan described himself as a socialist, and always gave generously of his time, and musical skills for causes he believed in. He was outspoken on many issues, in particular, Irish, Australian and other traditional/ethnic music and politics.

For his performance of political/ satirical songs he was often subject to warnings and censorship. He was banned from lunchtime concerts in Martin Place, Sydney, after singing 'The dying treasurer' by John Dengate. However, bans and censorship never deterred Declan, merely reinforcing his commitment to sing such songs in public. He'd never turn his back on such a challenge.

Reprinted with permission Trad n Now.

(Thanks to Bob Bolton for the photos)